Women have always known when something was wrong with their bodies. But for centuries, they’ve been told otherwise—by healthcare professionals, priests, scientists, and husbands. Pain was not pain; it was hysteria. Bleeding was not a symptom; it was punishment. Fatigue, swelling, breathlessness, confusion—none evidence of illness but of weakness, neurosis, lust.

The history of women’s healthcare is no well-intentioned climb toward omnipotence. It is an incomplete archive of dismissal, distortion, and outright violence. From ancient Greeks who believed the uterus wandered like a wild animal to 19th-century asylum doors that opened a little too easily for wives with opinions to modern exam rooms where women are still told their pain is “normal”—the throughline is mistrust, not benign misunderstanding.

As we trace the history of medical gaslighting (by the healthcare system, by our loved ones, and by our cultures), we encourage you to remember that this is not about bad science. It is about power. It is about who is believed and who isn’t. It is about how medicine—so often billed as “neutral”—has followed a cultural script, reinforcing who is seen as credible, coherent, and deserving of care.

Medical gaslighting is not new, but we’re naming it. And that is new.

What is Medical Gaslighting?

Medical gaslighting (also called “medical invalidation”) happens when medical professionals dismiss or minimize a patient’s symptoms and attribute them to anxiety, stress, or a mental health condition instead. This is often done without adequate testing, follow-up, or consideration of the patient’s own experience. It leaves patients—especially women, Black patients, and those from other marginalized groups—feeling unheard, invalidated, misdiagnosed, and without important medical care.

This isn’t limited to one bad doctor or one rushed medical appointment. It’s rooted in a larger healthcare system shaped by medical bias, limited time, and long-standing gaps in medical research. As you might imagine, we see medical gaslighting happen more frequently in relation to women’s health, chronic illness, and mental health. As Harvard Medical School researchers have noted, even when men and women present with the same symptoms, women are more likely to receive a diagnosis of a mental health condition, be prescribed less pain medication, or have their health concerns labeled as “stress-related.”

Classic examples of gaslighting in the medical system include women with IBD (inflammatory bowel disease) or IBS (irritable bowel syndrome) being told their pain is “in their head” or patients with long COVID, chronic pain, or mental illness being passed between specialists with no clear treatment. Those who rush to the emergency department with horrifying symptoms and unimaginable pain might be dismissed as “drug seeking” by health care professionals. Gaslighting is often associated with worse medical outcomes—especially in women.

You may be experiencing medical gaslighting if…

- Your symptoms are consistently dismissed without explanation.

- A physician tells you your test results are “normal” but you still feel unwell.

- You are not offered modern medical testing or appropriate referrals.

- You’re told to “reduce stress” or “get more sleep” as a catch-all treatment.

- You leave appointments feeling like you weren’t taken seriously.

The power differential between patient and provider can make it hard to spot medical gaslighting, but there are ways to protect yourself.

How to Protect Yourself from Medical Gaslighting

- Bring a trusted friend or family member to appointments.

- Write down your own experiences, symptoms, and questions in advance.

- Don’t hesitate to seek a second opinion—many patients need to advocate for themselves to receive quality care.

- Trust your own body. You deserve to feel heard.

Medical gaslighting is incredibly frustrating in the short-term but it can also have serious, lifelong consequences. Gaslighting can lead to worse health outcomes, delayed diagnoses, and improper or missed treatment. Recognizing that you have not received adequate care when you should have is your first step toward reclaiming self care, advocating for proper treatment, and demanding a more equitable health care system for all of us.

But this isn’t all on you.

Monsters, Myths, and Medical Men: Tracing the Timeline of Gaslighting in Women’s Healthcare

The Original Misdiagnosis of the Wandering Womb

Between the 5th Century BCE and the 4th Century CE, Western medicine did women few favors. The ancient Greeks believed the uterus was not an organ, but a creature. This create was unmoored, mobile, and hungry. According to Hippocratic theory, it could travel through a woman’s body, suffocating her organs, clouding her mind, and producing symptoms of madness. The solution? Scent therapy, sex, or marriage—tools meant to pacify the womb, not the woman.

This was not diagnosis. It was containment disguised as care.

The myth of the “wandering womb” is perhaps the earliest recorded instance of what we now call medical gaslighting, which you now know is when healthcare professionals translate a woman’s symptoms not as evidence of disease, but as proof of her instability, sexuality, or sin.

As Mary Lefkowitz wrote for The New Yorker back in 1996, “A woman who was unwell was said to be ‘womby.” Has much changed? Lefkowitz argues not. “Even today, when wombs have stopped wandering, medicine tends to pathologize the vagaries of the female reproductive system, from menarche to menopause.”

Not our bodies, not ourselves?

By the time Roman physicians like Soranus began writing gynecological texts, women’s bodies were already categorized by deficiency. Soranus, often considered progressive for his time, advised against overmedicating, yet still treated women almost exclusively through the lens of fertility. A woman’s body was not her own; it was a vessel, a womb, a means to an end, and nothing more.

Pain without pregnancy was often invisible. Illness without male distress was rarely real.

The Age of Authority and Asylums

Skipping ahead to the 18th century, we find ourselves face to face with Mary Wollstonecraft. Mary Wollstonecraft’s manifesto called for our access to education while ferociously rebuking the systems that kept women silenced, including medicine.

During this time period, male physicians routinely framed female intellect as a liability and female illness as emotional excess. Contrarily, Wollstonecraft issued a radical claim that angered her male counterparts: perhaps women were not weak but deliberately weakened.

Ignaz Semmelweis and the Unwashed Hands of Medicine

Decades later in 1847, Semmelweis observed a deadly pattern: women giving birth in physician-run hospitals were dying at alarming rates from childbed fever. The cause of these mass deaths was doctors moving directly from autopsies to deliveries without washing their hands. Semmelweis’ solution (basic hand hygiene), was dismissed as offensive, unscientific, even hysterical. While he did eventually implement chlorine hand-washing in one hospital, his 1861 book was ripped apart.

He died in an asylum. The women he tried to save died in droves.

Medical gaslighting doesn’t always look like disbelief in women’s symptoms. Sometimes, it is the refusal to take action when those symptoms are common, inconvenient, or coming from the “wrong” source.

The Father of Gynecology and the Mothers He Ignored

We often praise 19th century doctor J. Marion Sims as a pioneer of gynecology. Less often mentioned is how he built that legacy: through painful surgical experiments performed on enslaved Black women without anesthesia or consent. Their names—Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey—are remembered by few, but they are the true founders of the field.

Medicine’s advancements have often been paved with the suffering of those deemed expendable (women, Black patients, poor patients), whose pain was either normalized or invisible.

Hysteria, the “Rest Cure,” and the Architecture of Silence

As women began speaking more boldly—demanding rights, education, autonomy—medical professionals responded with a new diagnosis: hysteria. It could explain everything and nothing. Melancholy, ambition, sexuality, exhaustion, imagination—all were signs of feminine dysfunction.

The prescription was “the rest cure:” total isolation, no stimulation, no writing, no conversation.

Many of us are familiar with Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper from 1892, which is much more of a case study than a fictional tale. Written after Gilman herself was prescribed the rest cure, it exposes the insidious way medical care fails us. The unnamed narrator’s descent into madness is not caused by illness but by the very health care system designed to “treat” her.

Progress, at What Cost?

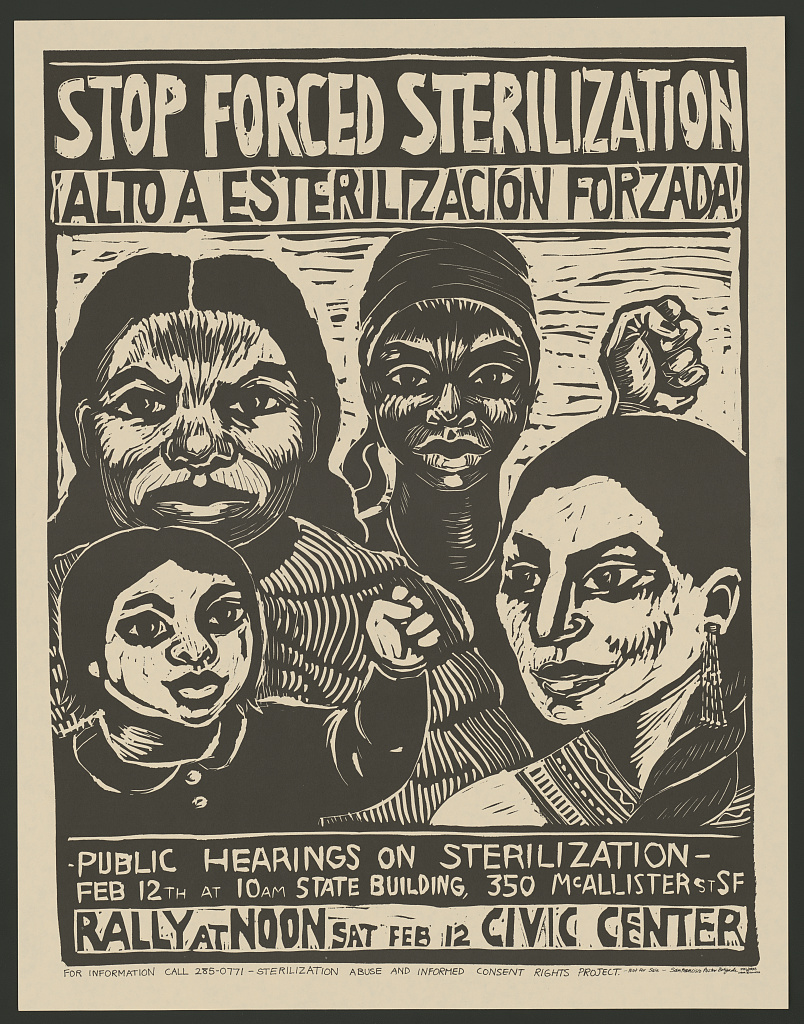

Under the banner of eugenics between the 1900s and 1930s, the U.S. forcibly sterilized over 60,000 people, primarily women of color, poor women, and disabled individuals, without consent. These procedures were framed as public good, even though we now see them for what they were: violation, maiming, and assault.

Women were experimented on, yet routinely left out of medical testing.

Just a couple decades later between the 1940s and ’60s, Thalidomide was marketed as a mild sedative and anti-nausea drug for pregnant women but caused thousands of birth defects worldwide. The scandal exposed what many already knew: modern medical testing rarely included women. Their own bodies were considered too “complicated” for clean data. The fallout was devastating and predictable.

Women were misinformed and minimized.

Around the same time, contraception became available to women. Often celebrated as a feminist breakthrough, the pill’s early trials paint a much bleaker picture. On the ground in Puerto Rico, poor women were recruited—often without full disclosure—and given experimental doses that caused severe side effects. Many healthcare professionals ignored or downplayed their reactions. There was no protocol for informed consent—only urgency to test.

And in the 1980s, Diethylstilbestrol (DES), prescribed to “prevent miscarriage,” harmed two generations. The drug caused cancer, infertility, and birth defects. Again, it was marketed as safe. Women’s concerns were ignored until the damage was irreversible.

The Price of Disobedience in Mid-Century and Postmodern Media

Over the last thirty years, we have reflected on medical gaslighting in film and on television. From Girl, Interrupted to The Crown, instances of medical maltreatment are endless. Cultural narratives mirrored real-life violations.

In Girl, Interrupted (set in 1967–68), young women are institutionalized and overmedicated for nonconformity. In Mad Men, Betty Draper’s depression is treated as an inconvenience. In The Crown, Princess Margaret’s struggles are sedated rather than understood.

These fictional portrayals echo a healthcare system that pathologized female emotion, autonomy, and illness while offering little in the way of proper treatment.

Present Day: The Pain Is Real—Are We Listening Yet?

Medical gaslighting persists, especially for Black patients, trans folks, women with “invisible” illnesses, and anyone outside the narrow model of the “ideal” patient. The maternal mortality crisis in the U.S. continues to produce worse health outcomes for women, especially women of color.

Long-dismissed conditions like PCOS, endometriosis, and long COVID are finally receiving attention, thanks to women-led advocacy and the democratizing power of social media. But medical understanding is still limited and treatments remain stuck in the past as funding is funneled elsewhere.

Educate Yourself. Advocate for Yourself.

If you need more information (and we’re sure you do), below are a few resources that might help. First, Maya Dusenbery’s Doing Harm investigates how bias in the medical system leads to worse health outcomes for women. Her words (and careful research) are incredibly validating. Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English’s For Her Own Good traces two centuries of medical and cultural control over women’s bodies.

Online communities like The Endometriosis Foundation of America, IWeigh’s health advocacy work, and hashtags like #MedicalGaslighting can connect you with other women experiencing similar health struggles and the dismissal that often accompanies them. Find support on Reddit and other forums if you can. For more clinical guidance, Harvard Health Publishing and Emergency Medicine News have finally started addressing these systemic issues in women’s health.

You are not imagining this. And you are not alone. But remember:

“Your silence will not protect you.”

—Audre Lorde

The featured image for this post is A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière by Pierre Aristide André Brouillet.

Leave a Reply